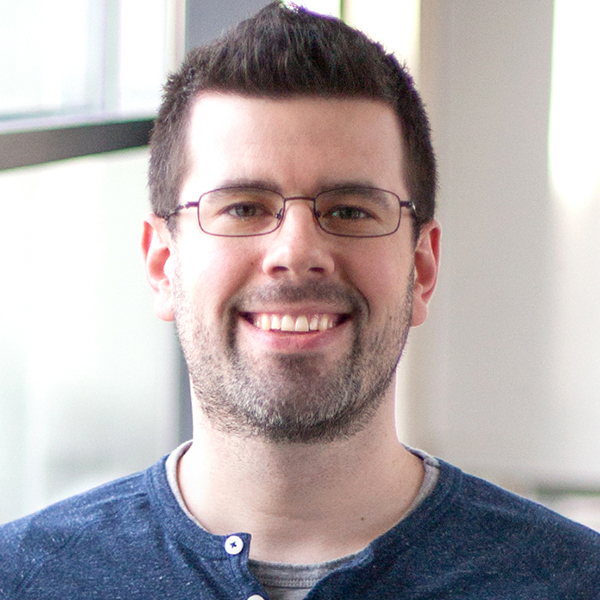

The old Kellogg School in Kellogg, Iowa

The Last Class at Kellogg School

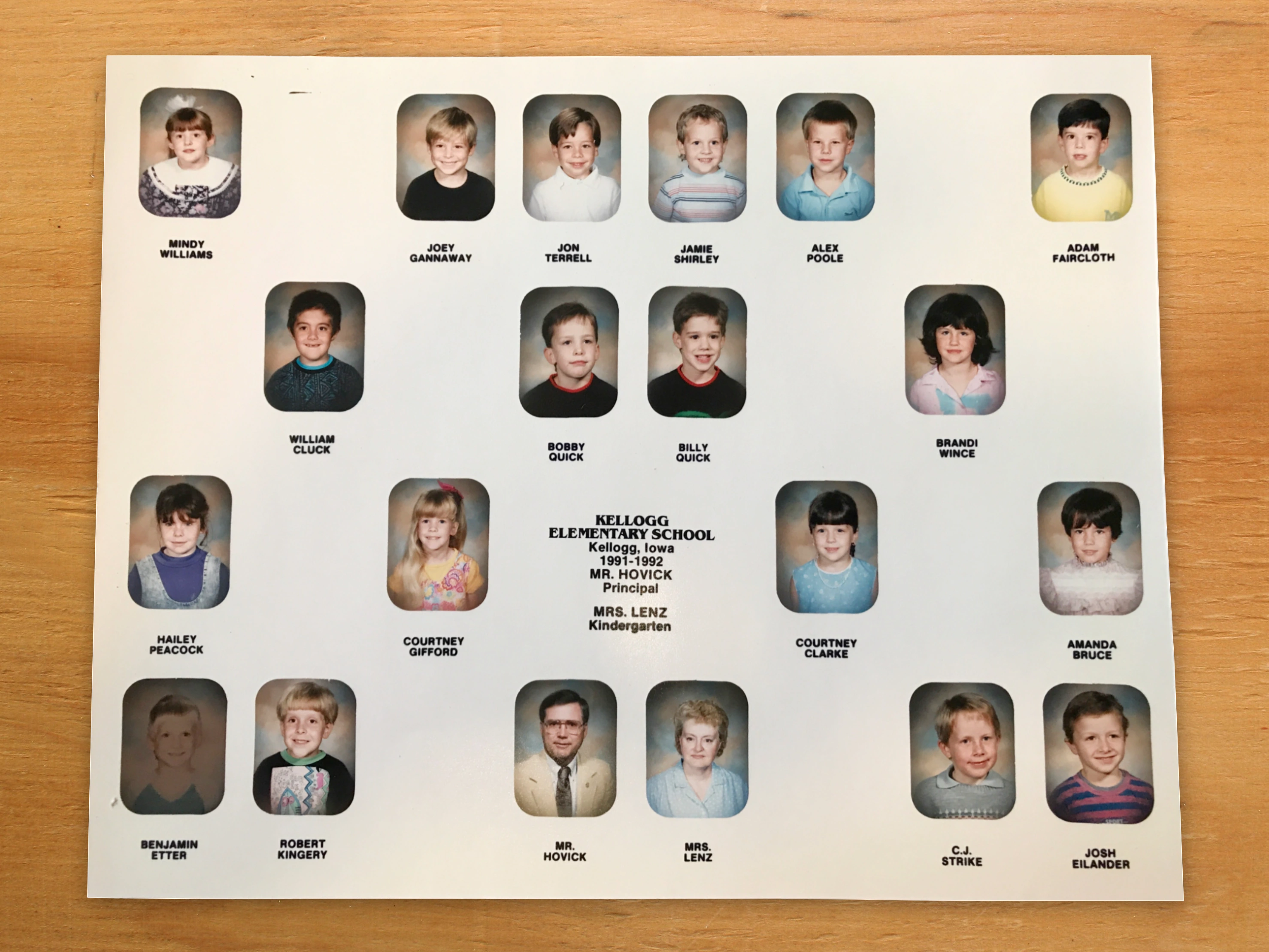

In the fall of 1991, I was a part of the new kindergarten class at Kellogg School. While none of us knew it at the time, we would be the last group of children to attend school in Kellogg.

Though my time at Kellogg School was short, I made many memories there. These memories are not all that unique to me, or to anyone from Kellogg for that matter. Yet, even though decades have passed, my mind can easily travel back to that place where I began.

On the first day of school, eighteen new kindergarteners were gathered on the floor waiting for class to start. Our kindergarten teacher that year would be Mrs. Sandra Lenz. The bell rang for the first time, and she walked in and sat in a chair at the front of the room. It soon became a dull roar as children were hollering, shouting to get her attention. Mrs. Lenz looked tentative, as if she might just stand up, turn around and walk out on us.

I watched the cacophony for a moment, and then a solution dawned on me. I'd been taught that I was supposed to raise my hand in school if I wished to talk. So I shot my hand into the air. The class immediately fell silent as my new classmates turned and stared at me. For a moment I thought I'd made an awful mistake, but Mrs. Lenz quickly praised my example of good school behavior. This cemented my identity as an obnoxious know-it-all.

Our classroom was on the bottom floor of what had been the old high school building. The walls in the hallway were painted green, and across from our room was the gymnasium. That school was so small, everything had to be done in the gymnasium. We went to art class in the gym, we had music lessons in the gym, and we ate lunch in the gym.

The school lunch menu cycled through a handful of reliable standbys like rectangle pizza or the ever-popular chili and cinnamon roll. I remember the colorful melamine lunch trays with little compartments for each item, and the tiny cartons of milk that we'd tear at until an adult came along to help us open them. Occasionally, someone's mom or dad would drop in to eat lunch with their child. Once, my cousins had a day off from junior high and stopped by to have lunch with me. I felt eminently cool, dining alongside distinguished guests.

The library was situated at the opposite end of the building, and for many of us it was our favorite place in the school. Descending the staircase at its entrance, the room itself imparted a feeling of reverence for the books inside it. I remember its rows of wood bookshelves, lofty ceilings, and expansive windows that looked out over the playground and the fiery autumn leaves of the timber behind our school. In my mind, we had two librarians: Mrs. Martha Ellsworth, and LeVar Burton, the host of Reading Rainbow. We spent meaningful time with each.

In the winter, we spent weeks preparing for the annual concert. We rehearsed Christmas songs with Mrs. Jane Johnson, the music teacher. All the sections of Mr. Rick Miller's art classes contributed to an enormous painting of Santa Claus that would be the backdrop for our stage.

My class on stage at the Christmas concert

In those days, the Christmas concert was held at night. It was a big event. There was something surreal and magical about going back in the school after dark. The building buzzed with excitement as families filed into the gymnasium. I remember standing with my classmates in our kindergarten room, wearing my wool sweater, waiting to go on stage. It felt like the entire town of Kellogg was in attendance, and they probably were.

When spring came, we walked down the hill to Holmdahl Park for our track and field day. It consisted of kindergarten-safe events like the three-legged race and shoe kick. It was organized by Mrs. Lois Boeyink, the phys ed teacher. When we took our fitness tests, because we had no track at our school we would run the mile outside on the blacktop. It took about a thousand laps around the blacktop to make a mile. To make things worse, it was on a slope. My shuffling around the schoolyard could barely be considered running.

We looked forward to the next school year, when we'd move up to the first grade and no longer be the youngest and littlest kids in the school. But when the next fall finally came, Kellogg did not have enough new kindergartners to fill a class. So those kids rode busses to Newton, while my class stayed with Mrs. Lenz for another year.

We even stayed in the same classroom for first grade. But this year, the kindergarten-size tables and chairs had been replaced with proper school desks. The toys had been taken from the playroom — which was, I think, a big closet — and in their place was a pair of Apple II computers. Those machines were already a bit out-of-date by this time, but they enjoyed plenty of use in our class. I remember the click-clack of the keys as I learned to type my name on the Apple II.

Even by this late date, we still had only a single telephone in the school which was in the main office. Kids assigned to office duty would run notes from the office to the classrooms, since there was no way to call.

Mr. Duane Hovick was our principal — part time. He was also principal at Aurora Heights School in Newton. This was fantastic for us, because for three days out of the week you could not be sent to the principal's office for bad behavior. And by the time Mr. Hovick was back in Kellogg, whatever you had done earlier in the week was likely to have been forgotten.

That year, we held a school-wide mock presidential election. President George H. W. Bush won our school, but it was little help to him as he lost to Bill Clinton in reality.

Kellogg would never again see a new class of kindergarteners. As my class advanced, the lower grades dropped off and our school dwindled in size. In its last year, Kellogg School housed grades 3–6. My class was now in the third grade, perennially the youngest kids in the school. Mrs. Nancy Bosma was the teacher that year; it was her first and only year teaching in Kellogg.

I would finish my elementary years at Woodrow Wilson School in Newton. To my delight, some familiar faces were there as well. Mrs. Lenz became the reading teacher, and Mr. Miller still taught art. Ms. Hazel Peterson, who had taught my mother and some of my cousins in Kellogg, would be my fifth grade teacher in Newton.

Kellogg School was gone, and we learned to weave ourselves into a much larger fabric in Newton. I lost touch with many of my Kellogg friends, but I made new ones as well.

The last class at Kellogg School

I graduated from Newton High School in 2004. The next summer, I attended the Kellogg Alumni Reunion with my grandfather, Earl Faircloth. He graduated from Kellogg High School in 1935. He was the oldest graduate in attendance; I was the youngest. I sat with my grandpa at the table of 1930s graduates.

Nobody there knew me, but many knew my grandparents. Some knew my dad, or my uncles. Others knew my cousins. Meeting them made it clear to me that our school had been the heart of our town. It was the glue that held all these people together — all of us who had attended that school, some as much as 70 years apart. Our school has been gone for some time now, and sadly the same can be said for many small towns across Iowa. And so I feel fortunate to have grown up in our little town with the school on the hill, if only for a short time, and to have been a part of the last class at Kellogg School.